A few weeks ago, pre-COVID-19, I was literally putting the finishing touches to a paper: “A review of major service change in the NHS in Scotland 2010 – 2019: Place, Pace, and Politics.” It was to be the cornerstone of a suite of papers, analysing the pace of change in NHS in Scotland including political dimensions, local context, the importance of co-production and factors influencing consultation response rates.

In part it was prompted by the excellent paper Transforming health care: the policy and politics of service reconfiguration in the UK’s four health systems, Stewart et al (2019) published by Cambridge University Press in 12 April 2019.

“It is impossible to close a hospital or change the way in which out-of-hours services are provided because of the political pressure that is put on the Government of the day.”

In their paper the authors highlighted that they found “examples where change proposals led to potential conflict and were never implemented, often damaging relationships along the way.” Moreover, they described how a ‘backlog’ of service change that was felt necessary in the NHS was too “difficult to accomplish politically.”

Perhaps most notably they stated: “while it might be relatively easy to reorganise NHS management closing a hospital does not seem to be easy at all.” Something that the Auditor General in Scotland also mentioned during most recent discussions in the Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Parliamentary Committee, around leadership and workforce challenges across the NHS in Scotland (March 2010).

“It is impossible to close a hospital or change the way in which out-of-hours services are provided because of the political pressure that is put on the Government of the day.”

In Scotland, there is a clear process around engagement and service change. NHS Boards are required by the Scottish Government to inform, engage and consult their local communities about proposed service changes particularly if it may have a major impact (Chief Executive Letter (CEL) 4 2010.

Proposals which are ‘major’ require a period of formal public consultation lasting for a minimum of three months. Scottish Ministers are responsible for deciding which proposed service changes will be approved, something Stewart et al (2019) suggested makes it even more political and challenging to deliver change.

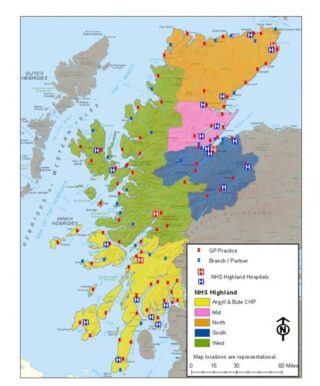

This seems to be borne out by the facts. Between 2010 to 2019, only six of the 14 territorial boards in Scotland attempted to consult on ‘major’ service change accounting for only 11 different proposals, four of which were by NHS Highland. Notably, not all the other board’s proposals received ministerial approval and included some consultations having to be repeated or stalled.

NHS Highland had all their major consultations approved. Our experience wasn’t that it was ‘impossible’ but rather even with excellent engagement, clinical leadership and board support, it took an awful lot of time to go through the process. Almost without exception, it created ‘noise’, protests, petitions, political (local) and sometimes staff opposition. While many ministers and others called to ‘speed up the pace of change’ paradoxically, one of the single biggest determinants to dictating pace were some of the political dimensions, in part responding to public feelings and concerns over possible changes.

Even in the face of the clear need to redesign services the process was often slowed down. The stark reality is to build a 24-bedded community hospital, as part of a wider redesign involving closing facilities has taken around a decade, and that hospital is still not complete.

NHS Highland had all their major consultations approved. Our experience wasn’t that it was ‘impossible’ but rather even with excellent engagement, clinical leadership and board support, it took an awful lot of time to go through the process.

It was within this context that I was reflecting on the new medical facility in London (Nightingale Hospital) initially with 500 beds prepared in a couple of weeks. And, similarly, the announcement this week that the SECC in Glasgow would be turned into a temporary hospital with an initial capacity of 300 beds within two weeks.

The pace of change and co-ordinated response is unparalleled on all fronts. Obviously, the context and circumstances are entirely different, but you do have to wonder what we can learn from this around speeding up the pace of routine redesign and modernisation of services.

As Professor Paul Gray, former Director General of Health and Social Care and Chief Executive of NHS Scotland (recently published in Reform Scotland, March 2020) put it: Whatever we do, please don’t commit to putting health and care services back to “the way they were” when all this is over. Sentiments I roundly support.

Next week I want to explore one of the most comprehensive public consultations carried out across the public sector in the UK and the role it played in gaining a public mandate to develop the Near Me service. And further reflect why despite collective, skilled and tenacious efforts, it has taken COVID-19 for the rollout process to ‘leap over hurdles that were apparently insurmountable a few weeks ago.’

Look out for part two of Maimie’s insights from NHS Highland, in the meantime you can find out more about NHS Near Me, which started out as a successful Q Exchange 2018 project on their website.

Article Source: https://q.health.org.uk/blog-post/covid-19-insights-from-highland/